“… sus diferencias frente al mundo. El ‘PACHUCO’ [colonized Mexican-Greaser] ha perdido toda su herencia: lengua, religión, costumbres, creencias. Sólo le queda un cuerpo y un alma a la intemperie, interne ante todas las miradas. Si disfraz lo protege y, al mismo tiempo, lo destaca y aísla: lo oculta y lo exhibe.”—Octavio Paz, El laberinto de la soledad y otras obras

Old or adolescent, Creole or mestizo, general, worker or graduate, the Mexican appears to me as a being that closes himself in and preserves himself: he masks his face and masks his smile. Planted in his surly solitude, prickly and courteous at the same time, everything serves to defend himself: silence and words, courtesy and contempt, irony and resignation. As jealous of his own privacy as of that of others, he does not even dare to touch his neighbor with his eyes: a glance can unleash the anger of those souls charged with electricity. He goes through life as if flayed; Everything can hurt you, words and suspicion of words. His language is full of reticence, figures and allusions, ellipses; In his silence there are folds, nuances, storm clouds, sudden rainbows, indecipherable threats. Even in dispute he prefers veiled expression to insult: “few words to the good understander.” In short, between reality and his person he establishes a wall, no less insurmountable because it is invisible, of impossibility and remoteness. The Mexican is always far away, far from the world and from others. He’s far, too, from himself.

Popular language reflects the extent to which we defend ourselves from the outside: the ideal of “manliness” consists of never “giving up” (Mexicanism: opening up, surrendering, cowering). Those who “open up” are cowards. For us, contrary to what happens with other peoples, opening up is a weakness or a betrayal. The Mexican can bend, humiliate himself, “crouch,” but not “split,” that is, allow the outside world to penetrate his privacy. The “rajado” is unreliable, a traitor or a man of dubious fidelity, who tells secrets and is incapable of facing dangers as he should. Women are inferior beings because, when they give themselves, they open themselves. Their inferiority is constitutional and lies in their sex, in their “crack,” a wound that never heals.

Hermeticism is a resource of our suspicion and distrust. It shows that we instinctively consider the environment around us dangerous. This reaction is justified if you think about what our history has been and the character of the society we have created. The harshness and hostility of the environment – and that threat, hidden and indefinable, that always hangs in the air – forces us to close ourselves off from the outside, like those plants on the plateau that accumulate their juices behind a thorny shell. But this behavior, legitimate in its origin, has become a mechanism that works alone, automatically. When faced with sympathy and sweetness, our response is reserve, because we do not know if these feelings are true or simulated. And furthermore, our masculine integrity is as much in danger from benevolence as from hostility. Every opening of our being entails a renunciation of our manhood.

Our relationships with other men are also tinged with suspicion. Every time the Mexican confides in a friend or acquaintance, every time he “opens up,” he abdicates. And he fears that the confidant’s contempt will follow his surrender. That is why confidence dishonors and is as dangerous for the one who makes it as for the one who listens to it; We do not drown in the fountain that reflects us, like Narcissus, but we blind it. Our anger is nourished not only by the fear of being used by our confidants – a general fear for all men – but by the shame of having given up our solitude. He who trusts, becomes alienated; “I sold out to so-and-so,” we say when we trust someone who doesn’t deserve it. That is, we have “cracked”, someone has penetrated the strong castle. The distance between man and man, creating mutual respect and mutual security, has disappeared. Not only are we at the mercy of the intruder, but we have abdicated. All these expressions reveal that the Mexican considers life as a struggle, a conception that does not distinguish him from the rest of modern men. The ideal of manhood for other peoples consists of an open and aggressive disposition to combat; We accentuate the defensive character, ready to repel the attack. The “macho” is a hermetic being, closed in on himself, capable of keeping himself and what is entrusted to him. Manhood is measured by invulnerability to enemy weapons or the impacts of the outside world. Stoicism is the highest of our warrior and political virtues. Our story is full of phrases and episodes that reveal the indifference of our heroes in the face of pain or danger. From childhood we are taught to suffer defeats with dignity, a concept that is not lacking in greatness. And if we are not all stoic and impassive — like Juárez and Cuauhtémoc [Refers to Benito Juárez (1806-72), Mexican patriot and president in two terms, 1858-61 and 1867-72, and Cuauhtémoc (1502?-1525), last Aztec king, who was tortured and murdered by the Spanish during the conquest of Mexico] — at least we try to be resigned, patient and long-suffering. Resignation is one of our popular virtues. More than the brilliance of victory, we are moved by [testicular] fortitude in the face of adversity.

Though somewhat obscure in the beginning, this subject shows the efficacy of a mother’s prayer. Holy is the name Mother, and many who stray from the path of righteousness to the radiantly alluring avenues of sin and prodigality, are rescued from the inevitable end by her prayers. So it is with the hero of this story. Jose, a handsome young MEXICAN[-GREASER], leaves his home in the ‘SIERRA MADRE’ [SERRATED MOTHER] MOUNTAINS to seek his fortune in the States. On leaving, his dear old mother bestows upon him her blessing, presenting him with a pair of gauntlets, upon the dexter wrist of which she has embroidered a Latin Cross. This she intended as a symbol and reminder to him of her and her prayers for his welfare. She cautions him to be temperate, honest and dispassionate: TO BEAR THE ‘BURDEN’ OF LIFE’S ‘CROSS‘ [The MOST HEINOUS of all CRIMES committable — the CRIME of having been born as a RUDDY-ARSE little MEXICAN-GREASER] with fortitude and patience.”

The Greaser’s Gauntlet (1908) Plot Synopsis

The preeminence of the closed over the open does not manifest itself only as impassibility and distrust, irony and suspicion, but as love of Form [The entire meditation on “form” echoes the sociology of Georg Simmel (1858-1918) See, above all, his Soziologie. Unter-suchungen über die Formen der Vergesellschaftung (1908), which Paz must have known in the Spanish translation of Simmel’s Sociology published in 1925 by the Revista de Occident]. This contains and encloses intimacy, prevents its excesses, represses its explosions, separates and isolates it, preserves it. The double indigenous and Spanish influence is combined in our predilection for ceremony, formulas and order. The Mexican, contrary to what is assumed to be a superficial interpretation of our history, aspires to create an order in accordance with clear principles. The turmoil and acrimony of our political struggles prove the extent to which legal notions play an important role in our public life. And in everyday life the Mexican is a man who strives to be formal and who very easily becomes formulaic. And it is explainable. The legal, social, religious or artistic order constitutes a safe and stable sphere. In its scope it is enough to adjust to the models and principles that regulate life; No one, to demonstrate, needs to resort to the continuous invention that a free society demands. Perhaps our traditionalism — which is one of the constants of our being and what gives coherence and antiquity to our people — is part of the love we profess for the Form. The ritual complications of courtesy, the persistence of classical humanism, the taste for closed forms in poetry (the sonnet and the tenth, for example), our love for geometry in the decorative arts, for drawing and composition in painting, the poverty of our Romanticism compared to the excellence of our Boroque art, the formalism of our political institutions and, finally, the dangerous inclination that we show for formulas – social, moral and bureaucratic – are so many expressions of this tendency of our character. The Mexican not only doesn’t open up; He doesn’t spill either.

The Bloody Island Massacre was a mass killing of indigenous Californians by the U.S. Military that occurred on an island in Clear Lake, California, on May 15, 1850. It is part of the wider California genocide.

A number of the Pomo, an indigenous people of California, had been enslaved by two settlers, Andrew Kelsey and Charles Stone, and confined to one village, where they were starved and abused until they rebelled and murdered their captors. In response, the U.S. Cavalry murdered at least 60 of the local Pomo. In July 1850, by Major Edwin Allen Sherman contended that “There were not less than four hundred warriors killed and drowned at Clear Lake and as many more of squaws and children who plunged into the lake and drowned, through fear, committing suicide. So in all, about eight hundred Native Americans found a watery grave in Clear Lake.”

wikipedia.org/wiki/California_genocide

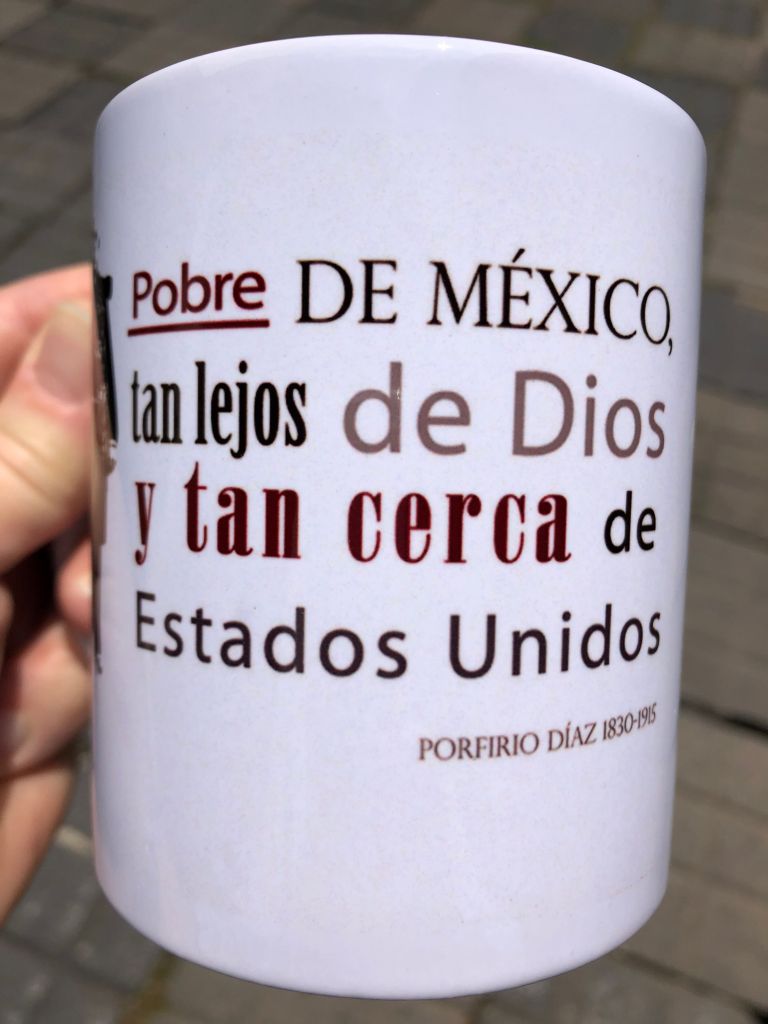

Sometimes shapes drown us. During the last century, LIBERALS vainly tried to subject the reality of the country to the straitjacket of the [LIBERAL] Constitution of 1857.

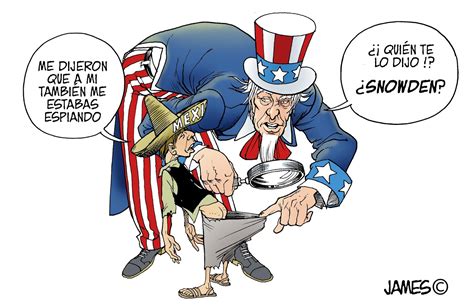

🚨 Klaus Schwab, Transgenderism, and AI | Russian Philosopher Aleksandr Dugin | Tucker Carlson

The results were the Dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz and the Revolution of 1910 [Refers, respectively, to the LIBERAL constitution adopted on 11 March 1857 with which the federal government was constituted, and the establishment of the representative republic; the Mexican caudillo (1830-1915) who governed Mexico between 1872 and 1910; and the so-called “Mexican Revolution” that reacted to the dictatorship of Diaz]. In a certain sense, the history of Mexico, like that of every Mexican, consists of a struggle between the forms and formulas in which we try to enclose our being and the explosions with which our spontaneity takes revenge. Rarely has Form been an original creation, a balance achieved not at the expense but thanks to the expression of our instincts and desires. Our legal and moral forms, on the contrary, frequently mutilate our being, prevent us from expressing ourselves and deny satisfaction to our vital appetites.

Defense against the outside or fascination with death, mimicry does not consist so much in changing nature as in appearance. It is revealing that the appearance chosen is that of death or that of inert space, at rest.

The preference for Form, even empty of content, is manifested throughout the history of our art, from pre-Cortesian times to the present day. Antonio Castro Leal, in his excellent study of Juan Ruiz de Alarcón [Refers to Juan Ruiz de Alarcón: His life and work of him (1943), which Paz reviewed for his publication; see PL, pp. 230-33], shows how the reserve towards romanticism – which is, by definition, expansive and open – is expressed as early as the 17th century, that is, before we were even aware of nationality. Juan Ruiz de Alarcón’s contemporaries were right when they accused him of being a meddler, although they spoke more about the deformity of his body than about the singularity of his work. Indeed, the characteristic portion of his theater denies that of his Spanish contemporaries. And his denial contains, in figure, what Mexico has always opposed to Spain. Alarcón’s theater is a response to the Spanish vitality, affirmative and dazzling at that time, and which is expressed through a great Yes to history and passions. Lope exalts love, the heroic, the superhuman, the incredible; Alarcón opposes these excessive virtues with other more subtle and bourgeois ones: dignity, courtesy, a melancholic stoicism, a smiling modesty. Moral problems are of little interest to Lope, who loves action, like all his contemporaries. Later Calderón would show the same disdain for psychology; The moral conflicts and the oscillations, falls and changes of the human soul are only metaphors that reveal a theological drama whose two characters are original sin and divine Grace. In Alarcón’s most representative comedies, on the other hand, the sky counts for little, as little as the passionate wind that carries away the Lopesque characters. Man, the Mexican tells us, is a composite, and evil and good subtly mix in his soul. Instead of proceeding by synthesis, he uses analysis: the hero becomes the problem. In several comedies the question of lying is raised: to what extent does the liar really lie, does he really intend to deceive?; Is he not the first victim of his deception and is it not himself that he deceives? The liar lies to himself: he is afraid of himself. By considering the problem of authenticity, Alarcón anticipates one of the Mexican’s constant themes of reflection, which Rodolfo Usigli would later collect in El gesticulator [Theatre play (1937) by the Mexican playwright Rodolfo Usigli (1905-1979). Its theme is the lie and its destructive consequences in the political life of Mexico and the private life of Mexicans].

In Alarcón’s world neither passion nor Grace triumph; everything is subordinated to reason; His archetypes are those of morality that smiles and forgives. By replacing Lope’s vital and romantic values with the abstract ones of a universal and reasonable morality, does he not evade, does he not hide his own being from us? The denial of it, like that of Mexico, does not affirm our uniqueness compared to that of the Spanish. The values that Alarcón postulates belong to all men and are a Greco-Roman heritage as well as a prophecy of the morality that the bourgeois world will impose. They do not express our spontaneity, they do not resolve our conflicts; They are Forms that we have not created or suffered, masks. Only until today have we been able to confront the Spanish Yes with a Mexican Yes and not an intellectual affirmation, empty of our particularities. The Mexican Revolution, by discovering the popular arts, gave rise to modern painting; By discovering the language of the Mexicans, it created the new poetry.

If in politics and art the Mexican aspires to create closed worlds — in the sphere of daily relationships — let modesty, prudence and ceremonious reserve prevail. Modesty, which is born from shame in the face of one’s own or another’s nudity, is an almost physical reflection among us. Nothing is further from this attitude than the fear of the body, characteristic of North American life. We are not afraid or ashamed of our body; We face it naturally and live it with a certain fullness — the opposite of what happens with the Puritans. For us the body exists; it gives gravity and limits to our being. We suffer it and we enjoy it; It is not a suit that we are used to inhabiting, nor something foreign to us: we are our bodies. But strange glances startle us, because the body does not see intimacy, but rather discovers it. Modesty, thus, has a defensive character, like the Chinese wall of courtesy or the organ and cactus fences that separate the huts from the peasants in the countryside. And that is why the virtue that we value most in women is modesty, as in men it is reserve. They must also defend their privacy.

Without a doubt, the masculine vanity of the lord intervenes in our conception of feminine modesty – which we have inherited from Indians and Spaniards. Like almost all peoples, either from man’s desires or from the purposes assigned to him by law, society or morality. Purposes, it must be said, for which his consent has never been asked and in whose realization he participates only passively, as a “depository” of certain values. Prostitute, goddess, great lady, lover, woman transmits or preserves, but she does not create, the values and energy entrusted to her by nature or society. In a world made in the image of men, women are only a reflection of masculine will and desire. She is passive, she becomes a goddess, beloved, a being that embodies the stable and ancient elements of the universe: the earth, mother and virgin; she activates, she is always a function, a medium, a channel. Femininity is never an end in itself, as is manhood. In other countries these functions are carried out in public light and with brightness. In some, prostitutes or virgins are revered; In others, mothers are rewarded; In almost all of them, she flatters and respects the great lady. We prefer to hide those graces and virtues. The secret must accompany the woman. But the woman must not only hide but, in addition, she must offer a certain smiling impassibility to the outside world. In the face of erotic dalliance, she must be “decent”; in the face of adversity, “suffered”. In both cases her response is neither instinctive nor personal, but conforms to a generic model (2nd Ed.: new passage, until end of paragraph). And this model, as in the case of the “macho”, tends to emphasize defensive and passive aspects, in a range that goes from modesty and “decency” to stoicism, resignation and impassibility.

The Hispano-Arab heritage does not completely explain this behavior. The attitude of the Spanish towards women is very simple and is expressed, with brutality and concision, in two sayings: “the woman at home and with the broken leg” and “between saint and saint, wall of lime and song.” The woman is a domestic beast, lustful and sinful by birth, who must be subdued with the stick and driven with the “brake of religion.” Hence, many Spaniards consider foreign women — and especially those who belong to countries of a different race or religion than their own — as easy prey. For Mexicans, women are dark, secret and passive beings. She is not attributed bad instincts: she pretends that she does not even have them. Better said, they are not his but the species’; Woman embodies the will of life, which is by essence impersonal, and in this fact lies the impossibility of her having a personal life. To be herself, the owner of her desire, her passion or her whim, is to be unfaithful to herself. Much freer and pagan than the Spanish — as heir to the great pre-Columbian naturalist religions — the Mexican does not condemn the natural world. Nor is sexual love tinged with mourning and horror, as in Spain. The danger does not lie in instinct but in assuming it personally. Thus the idea of passivity reappears: lying or upright, dressed or naked, the woman is never herself. An undifferentiated manifestation of life, it is a channel of cosmic appetite. In this sense, it has no desires of its own (“As strange as it may seem, women accept this belief, at least in public. And in certain cases it is possible that, in fact, their instincts sleep or express themselves through hints”).

Americans also proclaim the absence of instincts and desires, but the root of their claim is different and even contrary. The American woman hides or denies certain parts of her body—and, more often, of her psyche: they are immoral and therefore do not exist (1st Ed.: “her body: they are immoral and therefore they do not exist). By refusing, she represses her spontaneity. The Mexican simply does not have the will. Her body sleeps and only lights up if someone wakes it up. It is never a question, but rather an answer, an easy and vibrant material that imagination and masculine sensuality sculpt. Faced with the activity displayed by other women, who wish to captivate men through the agility of their spirit or the movement of her body, the Mexican woman opposes a hieraticism, a repose made at the same time of waiting and disdain. The man hovers around her, celebrates her, sings to her, makes his horse or her imagination whirl. She veils herself in modesty and immobility. She is an idol. Like all idols, she is the owner of magnetic forces, whose effectiveness and power grow as the emitting focus is more passive and secret. Cosmic analogy: woman does not seek, she attracts. And the center of her attraction is her sex, hidden, passive. Motionless secret sun (1st Ed.: “she is an idol. Modesty closes the world”).

This conception — quite false if you think that the Mexican woman is very sensitive and restless — does not turn her into a mere object, into a thing. The Mexican woman, like all others, is a symbol that represents the stability and continuity of the race. Its cosmic significance is combined with its social significance: in daily life its function consists of ensuring law and order, piety and gentleness prevail. We make sure that no one “disrespects the ladies,” a universal notion, without a doubt, but one that in Mexico is taken to its ultimate consequences. Thanks to it, many of the rough edges of our “man-to-man” relationships are smoothed out. Naturally, Mexican women would have to be asked their opinion; That “respect” is sometimes hypocritical to hold them down and prevent them from expressing themselves. Perhaps many would prefer to be treated with less “respect” (which, moreover, is only granted to them in public) and with more freedom and authenticity. That is, as human beings and not as functional symbols. But how are we going to allow them to express themselves, if our lives tend to become paralyzed in a mask that hides our intimacy?

Neither self-modesty nor social vigilance make women invulnerable. Both because of the fatality of her “open” anatomy and because of her social situation – repository of honor, Spanish style – she is exposed to all kinds of dangers, against which personal morality and intelligence, male protection can do nothing. Her evil lies in herself: by nature she is a “cracked”, open being. Furthermore, by virtue of an easily explainable compensation mechanism, she becomes a virtue of her original weakness and the myth of the “suffering Mexican woman” is created. The idol – always vulnerable, always in the process of becoming a human being – becomes a victim, but a victim hardened and insensitive to suffering, calloused by suffering. (A “suffering” person is less sensitive to pain than those who have barely been touched by adversity.) Through suffering, women become like men: invulnerable, impassive and stoic.

It will be said that by transforming something that should be a source of shame into a virtue, we only intend to discharge our conscience and cover up an atrocious reality with an image. It is true, but it is also true that by attributing to women the same invulnerability to which we aspire, we cover with her moral immunity her anatomical fatality, open to the outside. Thanks to her suffering, and her ability to resist it without protest, the woman transcends her condition and acquires the same attributes of the man.

It is curious to note that the image of the “bad woman” is almost always presented accompanied by the idea of activity. Unlike the “self-sacrificing mother”, the “expecting bride” and the hermetic idol, static beings, the “bad” one comes and goes, looks for men, abandons them. By a mechanism analogous to that described above, her extreme mobility makes her invulnerable. Her activity and impudence combine in her and end up petrifying her soul. The “bad” one is tough, impious, independent, like the “macho.” In ways, she also transcends her physiology and closes herself to the world.

It is significant, on the other hand, that male homosexuality is considered with a certain leniency, as far as the active agent is concerned. The passive, on the contrary, is a degraded and abject being. The game of “albures” — that is, the verbal combat made of obscene allusions and double meanings, which is practiced so much in Mexico City — makes this ambiguous conception transparent. Each of the interlocutors, through verbal tricks and ingenious linguistic combinations, tries to antagonize their adversary; The defeated is the one who cannot answer, the one who swallows the words of his enemy. And those words are tinged with sexually aggressive allusions; the loser is possessed, violated, by the other. The mockery and ridicule of the spectators falls on him. Thus, male homosexuality is tolerated, provided that it is a violation of the passive agent. As in the case of heterosexual relationships, the important thing is to “not open up” and, simultaneously, cut, hurt the opponent [Conceptual play on words, originally from Mexico, in which the sexual (or homosexual) reference implicitly implies the expiration of the other. For a concise description see A. Jiménez, Picardía mexicana, México, B. Costs Amic, 1958, pp. 222-5.]

IT SEEMS TO ME that all these attitudes, no matter how diverse their roots, confirm the “closed” nature of our reactions to the world or to our fellow human beings. But preservation and defense mechanisms are not enough for us. Simulation, which does not resort to our passivity, but requires active invention and which recreates itself at every moment, is one of our habitual forms of behavior. We lie for pleasure and fantasy, yes, like all imaginative people, but also to hide and protect ourselves from intruders. Lies have a decisive importance in our daily lives, in politics, love, friendship. With it we do not only intend to deceive others, but ourselves. Hence its fertility and what distinguishes our lies from the crude inventions of other peoples. Lying is a tragic game, in which we risk part of our being. That is why its complaint is sterile.

The simulator pretends to be what it is not. Its activity demands constant improvisation, always moving forward, amid shifting sands. Every minute we have to remake, recreate, modify the character we pretend, until there comes a moment when reality and appearance, lie and truth, become confused. From a fabric of inventions to dazzle others, simulation is transformed into a superior, artistic form of reality. Our lies simultaneously reflect our shortcomings and our appetites, what we are not and what we wish to be. Simulating, we get closer to our model and sometimes the gesticulator. As Usigli has seen deeply, he merges with his gestures, makes them authentic. The death of Professor Rubio makes him what he wanted to be: General Rubio, a sincere revolutionary and a man capable of boosting and purifying the stagnant Revolution. In Usigli’s work, Professor Rubio invents himself and becomes a general; His lie is so true that the corrupt Navarro has no choice but to once again kill his former boss, General Rubio. Kill in him the truth of Revolution.

If we can reach authenticity through the path of lying, an excess of sincerity can lead us to refined forms of lying. When we fall in love we “open up”, we show our intimacy, since an old tradition wants the one who suffers from love to exhibit his wounds before the one he loves. But upon discovering his love wounds, the lover transforms his being into an image, into an object that he gives to the contemplation of the woman—and of himself. By showing himself, he invites you to contemplate him with the same pious eyes with which he contemplates himself.

At all times and in all climates, human relationships – and especially romantic ones – run the risk of becoming misleading.

NARCISSISM AND MASOCHISM are not exclusive tendencies of the Mexican. But it is notable how frequently popular songs, proverbs, and everyday behavior allude to love as falsehood and lies. We almost always avoid the risks of a naked relationship through an exaggeration, originally sincere, of our feelings. Likewise, it is revealing how the combative nature of eroticism is accentuated among us and festers. Love is an attempt to penetrate another being, but it can only be realized on the condition that the surrender is mutual. This self-abandonment is difficult everywhere; Few agree on the dedication and even fewer manage to transcend that possessive stage and enjoy love for what it really is: a perpetual discovery, an immersion in the waters of reality and a constant recreation. We conceive love as a conquest and as a fight. It is not so much about penetrating reality, through a body, as about violating it. Hence the image of the lucky lover – inheritance, perhaps, from the Spanish Don Juan – is confused with that of the man who uses his feelings – real or invented – to obtain the woman.

Simulation is an activity similar to that of actors and can be expressed in as many ways as there are characters we pretend. But the actor, if he is truly an actor, surrenders to his character and fully embodies it, although later, once the performance is over, he abandons it, like the snake’s skin. The simulator never surrenders and forgets himself, because he would stop being a simulator if he merged with his image. At the same time, this fiction becomes an inseparable — and spurious — part of his being: it is condemned to represent his entire life, because a complicity has been established between him and his character that nothing can break, except death or sacrifice. . . The lie settles into his being and becomes the ultimate background of his personality.

TO SIMULATE is to invent or, better, to pretend and thus avoid our condition. Dissimulation requires greater subtlety: he who dissimulates does not represent, but rather wants to become invisible, to go unnoticed—without giving up his being. The Mexican exceeds in dissimulation of his passions and of himself. Afraid of the gaze of others, he contracts, reduces himself, becomes a shadow and a ghost, an echo. He doesn’t walk, he slides; he does not propose, he insinuates; He does not reply, he grumbles; he doesn’t complain, he smiles; Even when he sings — if he doesn’t burst out and open his chest — he does it under his breath and in a low voice, disguising his singing:

“And there is so much tyranny

of this dissimulation

that although of rare longings

my heart swells,

I have challenging looks

and voice of resignation”

(The verses come from “La tonada de la sierra enemiga” by Alfonso Reyes, collected in his Constancia poética, Complete Works, México, Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1954, X, 67.)

Perhaps dissimulation was born during the Colony. Indians and mestizos had, as in Reyes’ opinion, to sing quietly, because “words of rebellion are poorly heard between teeth.” The colonial world has disappeared, but not the fear, mistrust and suspicion. And now we not only hide our anger but our tenderness. When apologizing, rural people usually say, “Pretend it, sir.” And we hide. We disguise ourselves so carefully that we almost do not exist.

In its radical forms, dissimulation reaches mimicry. The Indian merges with the landscape, he merges with the white wall on which he leans in the afternoon, with the dark earth on which he stands at noon, with the silence that surrounds him. His human singularity is so hidden that he ends up abolishing it; and it becomes stone, pirú, wall, silence: space. I do not mean that he communes with the whole, in the pantheistic way, nor that in one tree he apprehends all trees, but that effectively, that is, in a concrete and particular way, he is confused with a determined object.

Roger Caillois observes that mimicry does not always imply an attempt to protect against virtual threats that swarm in the external world. Sometimes insects “play dead” or imitate the shapes of decaying matter, fascinated by death, by the inertia of space. This fascination – force of gravity, I would say, of life – is common to all beings and the fact that it is expressed as mimicry confirms that we should not consider it exclusively as a resource of the vital instinct to escape danger and death. . .